What is the proper word for the antidote for snakebite or scorpion sting, made from the blood of animals that have been immunized with venom? Toxicologists and reptile enthusiasts correct each other all the time, on social media. But is one term really more proper than the other?

Let’s start with the inventors of the original process, back when unpurified blood serum from immunized animals was first used as a drug. The movers and shakers in the field, when the concept was popularized, weren’t all writing in English.

Albert Calmette, in 1895, wrote a now-classic paper on the subject, titled “Contribution a l’étude des venins, des toxins et des serums antitoxiques,” in which he describes “serum antivenimeux.” That translates most closely to “antivenomous serum,” which sure enough is the word used in later translations of Calmette’s work, and in advertisements for the product in the USA. This use of “antivenomous” or, later “antivenom” as an adjective modifying the word “serum” continued for many years. In Mexico, in 1906, Daniel Vergara Lope echoed this phrasing in Spanish with the term “suero anti-ponzoñoso” in his paper on development of treatment for scorpion sting.

Also in 1895, a paper published by T. R. Fraser in the British Medical Journal was titled “the treatment of snake poisoning with antivenene derived from animals protected against serpents’ venom.” “Antivenene” at this time clearly referred to the same thing as “antivenomous serum,” and it remained the preferred spelling in a variety of British uses for many years. Both “antivenene” and “antivenin” were used as nouns from their first appearance, sometimes as a contraction of “antivenom serum,” and they were never hyphenated. A more general contraction was “anti-serum” or “antiserum,” which could refer to antivenin or to an antitoxin for infectious disease.

The use of “anti-venom” or “antivenom” as a noun did not always refer to the same specific substance as “antivenene” or “antivenin.” Todd, in 1909, published a paper titled “anti-serum for scorpion venom,” for instance, in which a section headed “Anti-venom” covers the broad concepts of protection against venom via active immunity, use of goat serum, and scorpion blood – meaning that the term was broader than “antivenin.” Other sources of that era use "antivenom" for potassium permanganate and other non-serum-derived treatments.

Hideyo Noguchi, who published a book in the USA on snake venom and treatment in 1909, consistently said “antivenin” to refer to what Calmette and others had made. He used the term "antivenomous” as an adjective. NY Times articles written around then mention “antivenene” and “antitoxin for rattlesnake bite.”

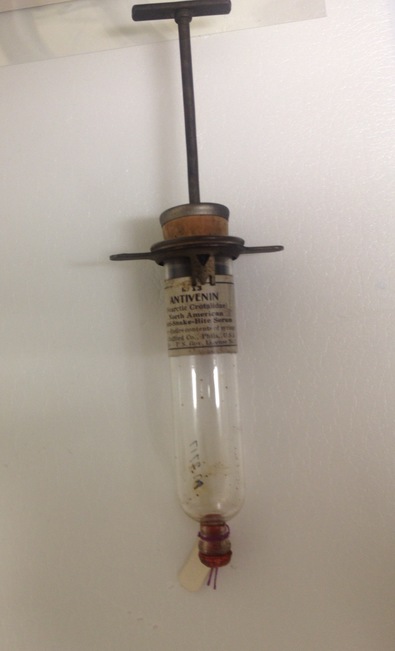

In 1928, the first rattlesnake-specific product marketed in the USA was referred to as “Antivenin (Nearctic Crotalidae) anti-snake-bite serum” by its manufacturer, Mulford Biological Laboratories. A related product, Lyovac Antivenin (Latrodectus mactans) was introduced in 1936. “Antivenin” was used in the manufacturer-defined names of a large variety of products from this time onward.

By 1930, however, the term “antivenom” had gained hold as a noun, describing essentially the same material as “antivenin.” Australian and South African products started being referred to as “antivenom” around that time.

By 1939, incremental improvements in manufacturing methods began to be made by manufacturers worldwide. Precipitation of extraneous proteins and albumin, enzymatic digestion of the antibody molecule, and addition of excipients gradually transformed the typical antivenom product so that it was no longer properly described as “serum.” Over time, some manufacturers switched methods of collecting blood from their horses, also, in order to return the red blood cells to keep the horses from becoming anemic. In order to do this, the blood was prevented from clotting, meaning that “serum” was never actually formed, and that the blood fraction called “plasma” was used instead. Manufacturers using these techniques preferred not to use the word “serum” any more, because it was no longer accurate.

By the 1950s and 60s, it became arguable whether the term “antivenom” should now be preferred (because it had always been broadly applied) or whether “antivenin” could refer to something more refined than simply “antivenom serum.” US professors who worked during this era taught my generation that the safest term to use was “antivenom,” because it was broader, and to use “antivenin” only when it was in the brand name. The only wrong spelling, they said, was with a hyphen; although I had one Australian professor who also forbade the spelling “antivenene,” because of poor relations with Great Britain following World War II.

The hyphen re-emerged from obscurity with the establishment of Microsoft’s spell checking software, which stubbornly refused to accept “antivenom” as a word in reports for newspapers and online stories throughout the 90s and early 2000s. This led to secondary controversy, suggesting that “antivenin” was correct and that “antivenom” was “not in the dictionary,” by innumerable lay sources.

Today, Wikipedia has an entry for “Antivenom” which begins “Antivenin (or Antivenom or antivenene) is…” and which implies that these three terms are synonymous. A World Health Organization publication following a 1979 international meeting states that “for use in English, ‘venom’ and ‘antivenom’ are considered to be the preferred names rather than ‘venin/antivenin” or ‘venene/antivenene.” “Yahoo Answers” claims that “antivenin” is preferred for the specific serum product and that “antivenom” still refers to general treatment. The Oxford Dictionary and Merriam-Webster allow either. “Urban Dictionary” lists neither.

Adding confusion to the public domain spelling, “Anti-Venom” in the Marvel Comic universe refers to Eddie Brock, originally a journalist covering Spider-Man, whose caustic post-cancer-treatment skin caused damage to a “Venom” symbiote that tried to reunite with him, under complicated circumstances. It then bound with his white blood cells, rendering “Anti-Venom.”

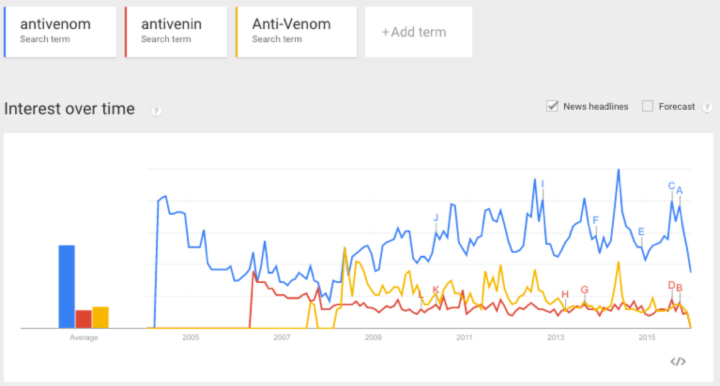

Finally, the general public weighs in, via Google Trends, where we learn that “antivenom” is a common search term in Australia, followed by Mexico, the US, India, Canada and the UK; “antivenin” is mostly a US term, and “Anti-Venom” is more Canadian than US. It is clear that in searches the spelling "antivenom" wins. You can see that the blue line (in the graph, below) even has greater seasonal trends, suggesting that searches for "antivenom" vary with the time of year when venomous snakes are active in the Northern Hemisphere.

Bottom line: it’s okay to say “antivenom,” “antivenin” or even “antivenene” to describe the blood product used to treat snakebite or scorpion sting. But resist the urge to hyphenate, Microsoft notwithstanding, unless you are a Marvel comics fan.

I'm a medical toxinologist, writing to make my field less scary and more understandable to people everywhere.