In a recent article, I re-examined data collected over 17 years by the American Association of Poison Control Centers, and I used it to construct a list of the Top Ten Exotic Snakebites in the USA. Exotic snakebites refers to bites by venomous snakes that do not naturally occur here in the USA. Over many years, the number of these creatures in US zoos, universities, museums and private collections has increased, because of their usefulness for development of new medicines, their fascinating biology, and their reptilian charm.

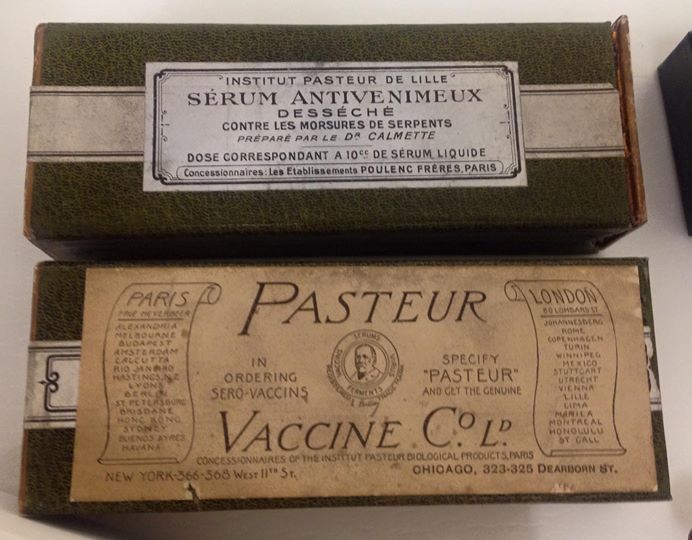

Owing to the special precautions taken in caring for these animals, bites by exotic snakes are extremely rare – a little over 40 per year, in the whole country. But accidents do happen, and responsible zoos and collectors prepare in advance by having the proper antivenom on hand. Member institutions in the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, for example, protect their employee’s health by keeping antivenom on hand from Africa, Australia, or wherever else in the world their particular animals come from. As I explained in a previous post, Antivenom in the USA, bringing these products into the country requires special permits, because most of the world’s antivenoms have not been formally proven safe or effective under FDA regulations.

Like other rare or so-called orphan drugs, antivenoms are sometimes expensive and occasionally very hard to find. This presents a special challenge in an emergency. In the off chance that a well-prepared zoo curator (say) is bitten during work hours, antivenom can be administered by medical personnel at the nearest hospital, perhaps an hour after the bite, and the curator will survive with minimal lasting injury. In the more common situation where an unprepared collector or scientist is bitten, however, it may take 24 hours or more for hospital personnel to contact Poison Control, identify the proper antivenom, and get the drug transported from a zoo several states away. Severe injury can occur, during such a delay.

The USA really, truly needs to get a national system together for doing this right. In the mean time, though, what if someone in your town is one of those rare 40 cases? What if they’re bitten by one of the animals on the Top Ten List? How prepared is your region, to track down the right antivenom and deliver it on time? To learn the answer, I reviewed inventory records representing about 10,000 vials of antivenom held in collections indexed by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, the Miami-Dade Fire Rescue's Venom Response Team, and the Kentucky Reptile Zoo, all of which have been kind enough, in the past, to share their precious antidotes with those who need them fast. I don't have records for all non-zoo holdings, because such records are private. In fact, most zoo folks don't want their availability advertised, because they tend to lose, rather than benefit, from helping the rest of us. In order to preserve the confidentiality of everyone involved, I've grouped the results into the same ten regions used by the United States Department of Health & Human Services.

Here's how the grading system worked: to score an "A," a region has to have plenty of antivenom in stock, to cover all of the "Top 10" list snakes for which antivenom exists. (This means that snake genus #10, the bush vipers, doesn't count, because nobody has invented that antivenom, yet.) In addition, an "A" grade means that the region has 24/7 emergency service to get the antivenom where it needs to go. And finally, it means that there is a system in place to ensure that zoo personnel are properly compensated for their time, that supplies are replenished promptly, and that legal mechanisms are set up to ensure that doctors, hospitals, paramedics and zoos are all appropriately integrated into the emergency system. An "A" region is ready to care for its emergency cases.

To earn a "B," a region has to have plenty of antivenom plus 24/7 emergency transport set up, but without any legal protection or replacement money for the used antivenom. A "B" region is prepared for emergencies, by mooching off its zoos.

In a "C" region, the antivenom is there, somewhere, if you know where to look; but good luck getting it transported at 2 am on a Saturday. "C" regions are not only mooching, they're risking serious delays.

In a "D" region, the amount of antivenom holders is pathetically small, relative to the size of the region and its population. Even if it had 24/7 transportation and financial incentives, a "D" region's people would be at serious risk after an exotic snakebite.

Finally, to score an "F," a US Public Health Region is seriously in trouble as far as exotic antivenom is concerned. In an "F" region, each of the "Top Ten" snakebites can be treated with antivenom borrowed from zero to one locations. So even if there is one place that keeps it, they might run out, or they might stop keeping that product -- and people in an "F" region would then have to scramble to borrow from a zoo at a much greater distance from home.

Okay then, by Region, in order:

Region 1: F. In all of Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Vermont, there is currently not one single vial of antivenom for the top ten exotic snakebites, visible to poison control centers through the antivenom index. Region 1 has some great resources: world-famous ivy league medical and public health schools; but not antivenom.

Region 2: D. Depending on which type of snake, there are between 1 and 4 holders of exotic antivenom for the entire region including New York, New Jersey, Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands.(None of those are in PR or the Virgins, which would be better off dealing with Region #4, anyway)

Region 3: D. The home base of the FDA and the NIH, this region spans Delaware, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia and the District of Columbia. Between 1 and 6 sites are available to share antivenom for each of the most common exotic snakebites.

Region 4: B-minus. The region that centers around CDC, encompassing Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and Florida, is well stocked with 4-9 holders of each necessary antivenom for the Top Ten. It moves up from a C to a B-minus because Miami-Dade Fire Rescue, at the southern tip of the region, maintains a unique 24/7 antivenom program serving its part of the region. Home to an assortment of private enterprises that serve the venom-supply needs of scientists and industry, Region 4 is better off than any other -- but tragically even this region lacks the infrastructural and funding support necessary to elevate its emergency system to an A.

Region 5: D. This is the midwest: Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio and Wisconsin. Each of the Top Ten snakebites can be treated using antivenom from between 3 and 9 sources -- but transport can still be a problem.

Region 6: C. Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Texas, and New Mexico are relatively well stocked, with 6-13 sources for each of the most common exotic snakebites.

Region 7: D. Iowa, Kansas, Missouri and Nebraska. 1-5 sites hold the antivenom, depending on the bite.

Region 8: F. Unbelievably, in the entire region covering Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Wyoming, Utah and Colorado there is not a single bite on the top ten list for which more than a single source is listed in the Antivenom Index.

Region 9: D. Arizona, Nevada, California, Hawaii and Pacific Islands. 3-4 sources for each listed snakebite (none of them on the islands). No dedicated transport system.

Region 10: F. Idaho, Oregon, Washington and Alaska can find antivenom for each of the top snakebites at either zero or one site. Plus, they're bordered by Regions 8 and 9 and they have no dedicated 24/7 program for shipping. Imagine being a midnight-shift doctor in Seattle, waking up a zoo herpetologist in San Diego or Dallas, and trying to settle the logistics -- while your patient is getting sicker.

In closing, I want to emphasize the tireless, heroic volunteer effort that has been sustained and called upon over many decades. Herpetologists and reptile collections managers across the USA are the de facto US antivenom pharmacopoeia. Without the generous efforts of some pretty amazing people, we wouldn't have an antivenom system at all. But the costs are going up, the antidotes are becoming more scarce, and the burden of bureaucracy is increasingly carried by a diffuse army of volunteers. It is well past time to acknowledge the public health importance of these essential drugs, to facilitate their acquisition and distribution, and to set up a system ensuring that no snake-bitten person in the USA is ever more than an hour away from a life-saving antidote.

I'm a medical toxinologist, writing to make my field less scary and more understandable to people everywhere.