On August 9, 2010, my assistant received an email message that began, “I am producing a documentary film about people who work professionally with venomous reptiles.” The message went on to describe an ambitious program of interviews from California to Canada, coast to coast, scheduled to continue through that November. The film would be “serious and educational (not sensational or hyperbolic).” Videography had apparently commenced only three days prior to the email; and an on-camera interview with me, covering 10 detailed questions, was requested for late October or early November. Unspecified broadcast, DVD sales, and online streaming were planned for January 2011. The message was signed, “Ray Morgan.”

If you’ve read Part 1 of this blog series, on what it is like to be an “expert” interviewed by reporters, then you should not be surprised that my office team greeted this message with a measure of trepidation. Media people doing stories about venomous reptiles are a fairly common lot, in our experience, and they tend to fall into the “opportunistic” and “quote-fishing” categories previously described. Here’s what I’m-doing-a-story-about-venomous-reptiles reporters usually ask me:

• Can we come get a photo of you “milking” a snake, or whatever it is you do that shows their fangs?

• What is the most venomous snake?

• How long do you, you know, HAVE, after you are attacked, before you die?

• Is it true there is a shortage? I forget what it is a shortage of. There is a shortage, right?

• Did I already ask you about the fangs? I have to get a fang photo, that’s the main thing.

(Side note to hurried reporters: I know you want me to wear a white coat and say “Yes, a scary Australian one, it’s an emergency, yes it’s terrible, here you go.” But those answers would be simplistic, inflammatory, and unworthy of an expert opinion. Besides, snakes are much more nicer photo subjects when they’re not biting a laboratory funnel.)

Something about this request, however, set it apart from the rest of the pack. This was an independent producer of valiant ambition and charming naiveté. Plus, he used the words “hyperbolic,” “envenomation,” “physiological,” and “Heloderma,” correctly spelled and in proper context. This Ray Morgan was a nerd on a mission.

We chatted that afternoon. Sure enough, Ray was a technologically sophisticated but amateur video producer. A lifelong reptile enthusiast in a career that had nothing to do with herpetology, he had – like me – been annoyed by news stories and TV productions whose “experts” spoke of snake “attacks” and showed off the scary fangs of the “most deadly” species. And he was determined to discover, and to tell, the “real” story about the scientists and animal managers that do genuine work involving reptile venom. Skeptical that he would succeed, but sympathetic, I agreed to provide Ray an interview at the end of his tour.

November 2010 came and went, without further word. Rumors of his tour reached me a couple of times, from colleagues across the southern US, but I heard nothing more direct until June of 2011, when Ray suddenly materialized in Tucson, Arizona. We rendezvoused at my parents’ home, in the desert north of town. He sounded tired, but with an evolved enthusiasm for his subject, having encountered common themes and perspectives that had forced him to rethink the entire project, for the better, along the way.

I was mildly guarded, at first, and might have tried to keep the proceeding brief; but we were interrupted before the interview could begin by the unexpected arrival of a snake, high in the tree outside the window. Abandoning the interview setup, Ray followed my mother out onto the patio, where he spent the next 40 minutes joyfully taking still shots of a handsome Masticophis flagellum, or coachwhip, several meters up. Quietly, doing as little as possible to disturb the snake, my erstwhile interviewer maneuvered around cacti and thornbushes to get every possible camera angle in the harsh summer sunlight.

This comfortable enthusiasm and patient photography in the heat of the desert afternoon won me over: much as he cared about his video production, Ray Morgan cared more about the animals themselves. By this point I was sweaty and disheveled; but that didn’t matter. I had confidence that this video producer, when he reached the editing phase, would do justice to his subject. A man with gentle respect for snakes in trees is a man one can trust to be kind.

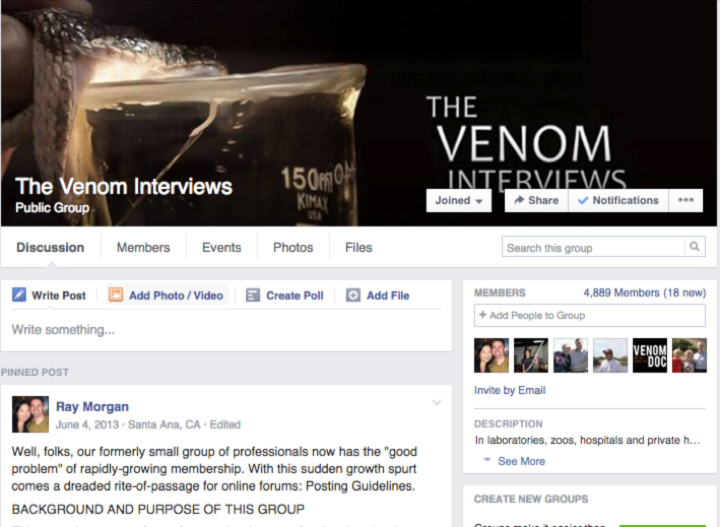

When we wrapped up the interview, several hours later, Ray acknowledged that his original timeline had been unrealistic. But now he was in so deep, having mesmerized so many people with the notion of telling the “real” story, that he had become obligated. He set up a FaceBook group called The Venom Interviews, which swelled quickly to several thousand members, where we could all nag him, comment, and follow along. The group became a magnet for scientists, zookeepers, hobbyists, doctors, and sundry others who today share stories of snakebites, safety advice for venomous snake work, and complaints about sensationalized television productions.

In preparation for this article, I contacted scientists and animal managers that I have come to know through this process, and I asked them to comment about the project: how was this experience different from other media experiences you have had? A flood of responses poured back, within 24 hours. The universal response, relief that it was not sensationalized, was as much an indictment of mainstream journalism as it was satisfaction with Ray’s work:

• “I was dubious, after a bad experience with [a major television studio].”

• “Not fishing for a sound bite or sensationalism.”

• “He had an interest in the real story.”

• “A breath of fresh air.”

• “This is in stark contrast to most interviews, where there is always a hint of suspicion as to how one’s comments and body language will be interpreted and presented.”

• “Refreshing change from the usual tripe.”

The second most common response was pleasure at Ray’s choice to avoid false balance, by excluding use of “experts” chosen specifically for their extreme views and actions. This practice has been far too common in science reporting, and – no surprise – genuine experts do not like being portrayed as less-flashy alternatives to snake-handling frauds. “It was nice to know you were going to be in a forum with… some of the best minds.” “Relieved to know that others presented would be peers and not… everything that is wrong with this field.”

Third and finally, several of the group expressed envy of Ray himself, for the luxury of his journey across the country. That luxury – to wander, to observe, to be immersed in wonder, and to bring people and ideas together –motivates many scientists from the beginnings of our careers. Few of us ever attain it, though, and so in that sense we have all been living vicariously through Ray, for the past 5 years.

Undoubtedly, Ray Morgan now feels pressure to turn out a masterpiece (and having previewed a late version I’m optimistic). But he shouldn’t worry. If the experts disagree in some way, about how he tells the story, that will be okay: scientists work through disagreements all the time; we’re okay with that. Besides, we know exactly where to have that conversation: in The Venom Interviews .

I'm a medical toxinologist, writing to make my field less scary and more understandable to people everywhere.