The earliest antivenoms were crude “antiserum” products. Antiserums were developed mainly in order to cure infectious diseases, such as diphtheria, in the days before we had childhood immunizations and antibiotics. Before the turn of the 20th century, antiserums produced from the blood serum of immunized horses saved many human lives. But they also had side effects, which were sometimes severe and occasionally deadly.

Records from the early 1900s reveal that doctors who treated patients with antiserums were concerned about three major patterns of adverse effect. These included dangerous allergic-type reactions (“anaphylaxis,” from the effects of a sudden jolt of horse serum in the human body), sudden fever-type reactions (from contaminants termed “pyrogens”), and delayed reactions (“serum sickness”). Over time, manufacturers learned ways to minimize the risk of pyrogens getting into the antiserum bottles, but the other two types of reaction remained common problems for many years. Doctors learned to be extra cautious about when and how they prescribed antivenom.

Parke-Davis received License Number 1, after the US began requiring biologics manufacturers to undergo safety inspections. Photo by L. Boyer, taken at the Smithsonian Museum of American History

Then one day in October 1901, five-year-old Veronica Neill was taken to a St. Louis clinic for care. Veronica had early signs of diphtheria, a disease that had been devastating up until the development of antiserum, just a few years earlier. Her doctor provided a dose of diphtheria antiserum, and everyone expected her to recover. But a horrible thing happened. Instead of recovering, the little girl came down with a second deadly disease, this time a brutally painful condition called tetanus. Three days later Veronica Neill was dead, her parents were distraught, and her doctor was deeply concerned at the coincidence.

The problem had not been pyrogens, or allergy, or serum sickness; but the coincidental timing after injection with antiserum was too much to ignore. Could diphtheria antiserum somehow have actually caused the tetanus infection? A fourth possibility had to be considered: what if the horse itself, the one immunized against diphtheria, had come down with a case of tetanus, and the tetanus was then transmitted in the blood plasma, all the way to the little girl in St. Louis?

Sure enough, when the drug was traced back to the manufacturer, it turned out that one horse, “Jim,” had been recently put to death because of illness. In a deadly oversight, the last batch of antiserum made using Jim’s blood had left the factory without the risk being recognized.

In the absence of a good tracking system with which to conduct a recall, thirteen St. Louis children died from tetanus, from injections of that one bad lot of diphtheria antiserum. Later that year, there were nine additional tetanus deaths, this time from a bad batch of smallpox vaccine.

The dangers of infected material threatened to overshadow the tremendous benefits of antiserum and vaccine use, and concern about the situation reached the halls of the United States Congress. With almost no opposition, Congress passed, and Theodore Roosevelt signed, a piece of legislation called the Biologics Control Act, authorizing the regulation of serums, vaccines, and anti-toxins by the predecessor of today’s National Institute of Health. Starting on July 1, 1902, companies that manufactured or sold vaccines or serum in interstate commerce were required to demonstrate their methods of preventing such problems during formal safety inspections – a requirement that continues to this day as a function of the FDA’s surveillance of commercially licensed antivenom and antitoxin manufacturing.

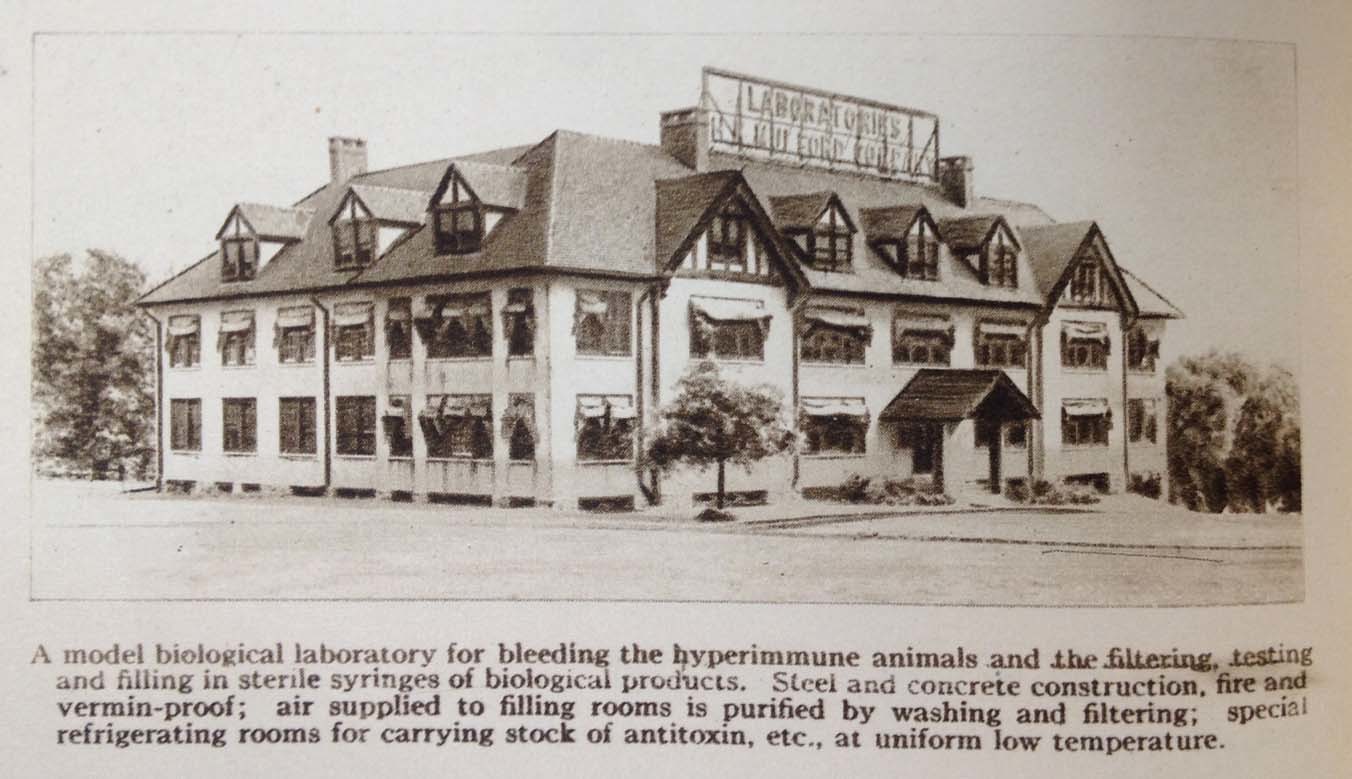

The Mulford Biologics building, in 1915. Mulford made a variety of antisera against infectious diseases such as diphtheria. Later they produced antivenom for treatment of pit viper bite. Illustration is from the 25th anniversary edition of The Mulford Digest, by the H.K. Mulford Company, Philadelphia, PA.

I'm a medical toxinologist, writing to make my field less scary and more understandable to people everywhere.