Properly, scientists call red-tailed hawks Buteo jamaicensis, but Sonora was a special creature and she had a name of her own, given by the trainers at the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. Sonora was four years old, she weighed two and a half pounds, and she knew every part of the museum that was visible from the sky. Flying was her life. When her veterinarian called me, however, Sonora was very much earthbound.

_______________________

The crate opens and Sonora is facing the tall saguaro cactus. The air is warm and dry. The sand here is hard and covered with rocks. Sonora takes flight, pulling hard with her wings but breathing easily.

Unlike humans and rodents that never leave the ground, Sonora has a chest and belly that share a single internal cavity. When Sonora inhales she fills sacs in her abdomen with fresh air, and when she exhales the sacs expel that air through a labyrinth of passages. This way, the tiny blood vessels of her compact lungs can draw oxygen constantly, regardless of how hard her chest muscles work.

Sonora lingers on the saguaro’s crown for several minutes, her talons and toes spread out to distribute her weight across the rows of sharp spines. Then, with a firm push, she extends her wings and leans forward. She dips only slightly, then cruises around the museum with slow, deep beats. On such a warm day she is sure to find a thermal somewhere.

Beyond the saguaros and rocky hills, sunlight shimmers off the tops of buildings and vehicles. There are humans in the distance, too, but they are not shiny. They are dull, like doves and coyotes. Sonora looks down, scanning the sand below for signs of movement by squirrels, packrats, or pocket mice. Maybe something interesting will move out from under a cactus.

Maybe she will dive, to catch something soft that she can squeeze with her talons and toes. But she has never had much luck with rats.

Daniel and Amanda hold out leather gloves on their arms where Sonora can land. The trainers are warm and make reassuring noises, and they always have fresh meat that tastes of quail or rodent. They will give her the meat, which she can eat right away, without having to pull out any feathers. Maybe she will let them have her catch, which most of the time is still alive, and they will release it back into the desert. If the prey is injured they might take it to the clinic for Dr. Siegrist to examine.

Sonora likes Daniel and Amanda better than Dr. Siegrist. Dr. Siegrist does not have quail meat. Instead she has cold, hard objects that she presses against animals’ bodies, in a skyless enclosure full of shiny boxes and strange noises.

Ever since last fall, Sonora has been a specialist. Other hawks sometimes specialize in catching small birds or rodents. For Sonora, there is something about reptiles, especially snakes. Is it because they are long and shiny and easy to spot from the heights of a thermal? Is it the excitement of crashing and rolling through the undergrowth, gripping a gopher snake in the talons of both feet at once? Is it the challenge of battle with coiled rattlers, using the long feathers on her wingtips as lures while she strikes behind the head? Sonora does not explain her reason. She simply specializes in snakes.

Sonora circles the museum, above a clearing in which fifty or so humans are clustered. She can see Amanda with them, wearing a microphone. Daniel is apart from the crowd, crouching near the ground. He has no glove. Up, then.

Sonora soars above the clearing. “See how she is moving in an upward spiral,” says a box attached to a post. “We have recorded this hawk riding a thermal air column as high as 3500 feet. That is out of sight even with binoculars.”

Sonora soars almost motionless above the receding chatter of cameras and human voices. Direct sunlight warms the upper side of her wings, while the thermal pushes gently from below. Patterns form among the receding objects below, spaces between cactus and creosote bush. A mouse hops twice, then vanishes into a hole.

Movement beside a mesquite tree catches her eye. It is a large creature, larger than any prey she has tackled before. It glistens in the midday sun. It is a snake.

More movement: Daniel has stood up from his crouch. He has the glove. Down, then. Down is good. She will go for the big snake. She angles downward, pulling hard, then tucks her wings close.

The sound of the box on the post crackles as she approaches. “…typically 20 to 40 miles per hour, but she can reach 120 during a dive like the one you are witnessing now.”

The crowd passes out of sight behind a hill, and in a crush of writhing scales and outstretched talons Sonora lands, directly on her reptilian target.

_______________________

Daniel missed her the first time he walked past. The second time, he spotted a wing protruding from a tangle of reptile and feathers. A big snake was wrapped several times around Sonora’s body and neck. Its head was broad, almost triangular, at first glance resembling that of a rattlesnake. Daniel radioed that he had found her, then he hesitated, wanting to intervene but unsure how to begin. In nature, large snakes sometimes eat birds. Putting your hand between battling predators is generally not a wise choice, particularly if one of them might be venomous. Daniel grabbed a wooden rib from the fallen skeleton of an old saguaro cactus. He used the rib to pin the snake’s head to the ground.

Amanda arrived, having dismissed the crowd. She had worked with reptiles as well as birds, and right away she recognized that the pinned animal was a gopher snake. She began pulling and untwisting it from around Sonora’s neck and chest. Constriction was a different form of attack from a rattlesnake’s strike, and it was a specialty of the desert’s non-venomous snakes. Sonora was in serious trouble, and it took both of them working for several minutes to disentangle her. They hid the snake in a sack. It was injured and would need care. Sonora was irritable, so they placed her back on the ground.

Sonora rose onto her feet. She stomped aggressively and searched the nearby sand, as if still looking for the gopher snake. Nothing seemed to be broken. She might even be well enough to perform again tomorrow.

Perhaps this brush with death would serve as a lesson, a warning not to tangle with snakes in the future.

_______________________

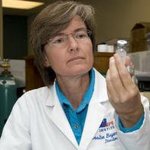

My primary medical board certification is in Pediatrics, but when Audrey Siegrist called I was editing a manuscript about what happened to snake venom in a sheep treated with antivenom made from the blood plasma of a horse. That might sound a little crazy, but learning from a variety of animals is fundamental to my job as a university professor. In nature, venomous creatures evolved alongside predators and prey animals of many kinds, so venom does a variety of very specific things to blood, nerves and other tissues of animals. For doctors to understand what happens inside a snakebitten person, we need to pay close attention to what happens in creatures similar to and different from us.

Dr. Siegrist said she had a red-tailed hawk in critical condition, in the museum’s veterinary examining room. The patient was one of their trained birds, a mature female red-tailed hawk. Apparently at the end of a public demonstration, the hawk had been found in possession of a snake, the second time in two days. Yesterday’s prey had been a gopher snake. Today, though, she had tangled with a Crotalus atrox, or Western Diamondback Rattlesnake, approximately 3 feet in length. It appeared to have been freshly killed and it was missing its head.

The patient’s right leg was swollen, and it had marks that might have been caused by fangs. Unfortunately she also had marks from “footing” herself with a talon during a different injury the day before, and it was difficult to know for sure how much of what they saw now was from this event. It was important to figure out whether any venom had actually entered her body. Then, if it had, Dr. Siegrist needed to know if antivenom would be useful, how to administer it, and what to expect in the way of side effects in a bird of prey.

Parts of this story sounded familiar. As a doctor who manages a lot of snakebites in humans, I knew that rattlesnake fangs do not always leave easily-recognized marks. As a pediatrician I was familiar with the problem of non-verbal patients and incomplete stories.

I am not trained in veterinary care, however, and there were many questions in this situation that I was unable to answer. Dr. Siegrist and I wondered: are birds of prey protected from venom by natural immunity of some kind? Maybe the hawk would do fine without our help. Or: if they are vulnerable to rattlesnake venom, then would it affect their blood the same way it affects the blood of humans and sheep? Most importantly: if they are vulnerable, and if this patient were to get sick in the next hour, would antivenom made using horse plasma be the right treatment? Or are hawks sometimes allergic to horses, in which case how could we make sure that the treatment itself did not kill this little patient?

The first answer, about natural immunity, might become clear within a few hours. If the hawk became dangerously ill, we would know she was not immune enough to matter. For practical purposes, we decided to prepare for the worst.

Sophisticated blood tests were not an option at the tiny museum clinic, but it would be useful to know if the bird, like human patients, was at serious risk of bleeding. I thought about a clever blood test that an African colleague once taught me, one that could be done without a fancy lab. If you put a small amount of normal blood in a clean, dry glass test tube, and you wait half an hour, it should firm up into a clot that will not spill out when you turn the test tube over. On the other hand, if you turn the tube over and the blood runs like water then you know that something is wrong with the clotting system.

Dr. Siegrist said she had the right kind of test tube and might be able to try this blood test, but she was worried about hurting the bird. Collecting blood would require making her hold very still, either by physical restraint or by putting her on life support – and both of these choices sounded potentially harmful.

The third question was about antivenom, and I suspected I knew enough to answer it. You can use the same kind of antivenom in humans, dogs, cats, and many other animals, because it works by neutralizing the venom, not by interacting with the patient directly. Dr. Siegrist said she would send for a dose of it, right away.

We didn’t quite make it to the last question on the list, though. Dr. Siegrist was interrupted by a person I could not see. “Sonora is going into respiratory failure,” she said. “Using a regular machine ventilator on a bird is very tricky, because their anatomy is so different from ours. But I need to try, because all of a sudden she looks really bad.”

And Dr. Siegrist ended the call.

_______________________

Sonora is wearing a hood. Someone warm carries her. Under the hood she is calm, but she can hear and feel people moving nearby. She is tired, her head droops, and her foot is bleeding where she scratched at it after the snake bit her.

A mask presses over her beak, and air flows past. Feathers around her eyes are out of place, but she is too weak to care. Something sharp pierces the skin of her chest, then something hot happens in the same spot.

Breathing becomes difficult. Her heartbeat is irregular, fast for a while, then slow. She wants to fly away, but she cannot move. Then something changes in the mask, and she feels strangely sleepy.

_______________________

Dr. Siegrist called me back, shortly after connecting the hawk to the mechanical ventilator. The clotting test, conducted on a tiny sample of blood from a wing vein, confirmed that venom was now circulating in her blood. The antivenom was due to arrive, at any minute.

I had spent the time between calls contacting colleagues to ask if anyone knew about the use of antivenom in birds of prey. Falconers in California had told me that snakebite usually kills birds too quickly to for them to arrive at a clinic. A toxinologist in Mexico told me about the use of antivenom in reptiles. A veterinarian in Argentina knew something about snakebite, but not antivenom, in eagles and chickens. There was some published research involving pigeons, but it did not apply directly to our situation with the red-tailed hawk.

We agreed that it was worth taking a chance, despite the uncertainty, because without antivenom it was very likely the patient would not survive. Without any clearer guidelines, I drew on my pediatric experience. I suggested to Dr. Siegrist that she should prepare for a possible allergic reaction, by having a dose of epinephrine ready in advance. (Epinephrine is also called adrenaline, and it is the so-called “fight or flight” chemical.) I recommended using a very small amount of water to dilute the powdered antivenom, so as not to over-fill the patient’s tiny blood vessels, then injecting it very slowly into a vein. I also warned that the veterinary team should watch closely during injection of the antivenom, for any signs of trouble.

As the antivenom injection started, I stayed on the line. Nothing seemed to happen as the first drops of antivenom went in. I mentioned the importance of getting a second blood test, later, for comparison with the first. The result might be helpful for deciding whether to give a second dose of treatment.

Abruptly, I heard anxious voices in the background, calling for help. Dr. Siegrist said, “oh no, she’s in cardiac arrest! Who knew there was such thing as a hawk allergic to horse serum.”

The phone line went silent, for the second time. I sat for a while, grieving the loss, feeling sad for my friends at the museum, and trying to imagine what we might have done differently.

_______________________

Her heart is going very fast. There is something irritating the underside of her left wing, but it is nothing compared to the annoyance of something in her throat. She is still wearing a hood and can see nothing. Amanda’s voice is there, though, and Daniel’s. Sonora feels heavy, and very weak.

There is movement, then, and something cold pressing on her chest. Then relief as her wings fold in closer to her chest. Someone holds her, upright against a warm place – Daniel, maybe? She is weak, though, and her head droops, and the throat thing is still there. Minutes pass, and the cold thing comes back. Someone counts, “one, two, three!” and the throat thing goes out.

Sonora vomits up the remnants of a rattlesnake head. Then Daniel removes the hood, and Sonora spreads her wings, but the room is too small for flying.

_______________________

“Not only is the patient already trying to fly, but the second blood test came out perfect!” Dr. Siegrist said when I picked up the phone several hours later. “Somehow, we managed to get in exactly the right dose, before she had the cardiac arrest, and the epinephrine brought her right back. We had to adjust her fluids after that, and her cardiac rhythm fluctuated for a while, but we extubated her already and she looks great. If it weren’t for the swollen foot, looking at her you’d think nothing had happened!”

Sonora continued to regain strength quickly. I went in to meet her when she returned to doing free flights, and I started working more closely on treatment protocols for future use by Desert Museum staff.

Several months after the snakebite, her soaring height and flight time were back to the same as before. Daniel and Amanda had to make one adjustment in her performance schedule, however. These days, Sonora flies only on cooler days – because at warmer times, when reptiles are active, she still prefers diving for snakes.

I'm a medical toxinologist, writing to make my field less scary and more understandable to people everywhere.