I’m a doctor, specializing in Toxinology. I study the effects of venom.

Every year or so, something happens that raises public interest in venomous snakes: a scary story is circulated, or a show presents an overly-dramatic notion of venom as “liquid gold,” or an expensive hospital bill for antivenom goes viral. On these occasions I tend to get a sudden flood of inquiries from naïve, but enthusiastic, people who have a generous thought: would it be helpful for them to catch some snakes and collect the venom, to use in research? Often, they mention their willingness to give me a good deal, less than some very high price that the actors mentioned in a video.

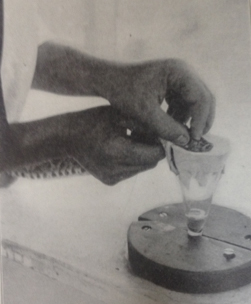

Rainforest harvest: a man in Honduras collects venom for use in the production of antivenom. (Source: 16th Annual Report of the United Fruit Company, Boston, 1927)

My first thought is to say, “thank you, but no.” This is because I’m a doctor, and the whole reason for my research is to alleviate suffering, not to cause it. I worry that well-intentioned beginners will get bitten and be badly hurt. Also, it is very easy for inexperienced people to cause harm to their animals.

On the other hand, somebody has to collect the venom used in science and technology. Here, I’m not referring to an impulsive guy that watched an exciting show then pounced on a backyard diamondback; I’m talking about a thoughtful, dedicated person who cares about reptiles, appreciates science, and has the ability to invest time and money. What should that person know, who genuinely wants to enter this very unusual field? Here are 7 things to think about, before starting:

1. Don’t believe everything you see in the media. There are important differences in what is depicted in investigational reporting, informational documentaries, and mass-market entertainment. For starters, many venoms are not actually in short supply; and contrary to what you might have heard, prices are mostly rock-bottom low. You might want to check what people already working in the field have to say, in the video documentary, The Venom Interviews, coming out in 2016 from Code Rica Media.

2. Read up. Believe me, you are not the first person to think of this, and you can benefit a lot from the experience of people already in the field. One excellent reference is Chapter 5 (Maintaining Venomous Reptile Collections) of the book Venomous Reptiles and their Toxins, published in 2015 by Dr. Bryan Fry. You should also find good books and articles on the animals and the venoms that interest you most. Find out what the venom does, and who is publishing research involving it. Learn to use PubMed, so you can find out who is using which venoms in current scientific and medical research.

3. Get proper training. Rules vary from state to state, but in general this means find a mentor who has been in the business for a while, get a grip on your ego, and be ready to work hard and accept criticism. Not sure where to find a mentor? Join your local herpetology club. Take a herpetology class at your local college. Get to know people at your local zoo. Get on FaceBook and join a few special-interest groups -- search on the words that relate to the animals you know best. Build a network. Respectfully, ask for help finding a mentor.

4. Talk with your doctor in advance. Venomous snakebite is a serious emergency. Unfortunately, most doctors are not trained in how to handle it. If you’re not sure about this, read my previous article, Tips for venomous animal enthusiasts looking for the right doctor.

5. Be safe. In addition to finding the right doctor, you should plan to use all the right gear, have emergency protocols in place, check that your insurance covers occupational injury, design your workplace to withstand power shortages and other equipment failures, stock up on antivenom, and know how to deal with your animals’ nutritional and veterinary needs without getting bitten. Again, Dr. Fry’s book lays out a lot of details related to this; and your mentor will take you through the process.

6. Brace yourself for unexpected costs. For instance, you are going to need refrigerator and freezer space that is not shared with your food. You’ll need access to a lyophilizer (a freeze-drier) for the venom. Some materials will need to be sterile, which means either a system to clean them or pricey disposables. Even if you try hard to be safe, you may get bitten, or become allergic to snakes, which means big medical bills. Be aware that successful venom collection operations don’t always bring in enough money to pay the owner a salary – for example, see this story about Jim Harrison at the Kentucky Reptile Zoo.

7. Follow the rules. Beware! University and pharmaceutical industry customers will need to know that they are dealing with a product they can count on to hold up under federal rules. In addition, laws governing how you work with venomous animals, with wildlife in general, and with snakes that are not native to the USA vary widely from state to state. Like it or not, you will be working under permits and regulations related to USDA, FDA, USFWS, CITES, and NIH. If you export venom, or import antivenom, there are international rules to consider. If any of these things sound unfamiliar, then go back and think about items 2, 3, 4 and 5.

In the past decade, I’ve obtained venom from 8 sources, only one of which had been established for less than ten years. In that time, people at three of those places were bitten – and thank goodness, they had protocols and antivenom on hand. Five of these sources donated the venom to my lab free of charge, in exchange only for collegiality or because of shared interest in a public service. And zero transactions involved Animal Planet or Discovery Channel productions.

So, back to whether or not I buy venom from enthusiastic beginners: unless you have already considered everything on this list the answer is thank you, but no. Venom may be golden colored, but it’s not really gold.

I'm a medical toxinologist, writing to make my field less scary and more understandable to people everywhere.