What is going on with the shortage of antivenom in Africa?

Discontinuation of Sanofi Pasteur's Fav-Afrique brought attention to a longstanding shortage of antivenom in sub-Saharan Africa.

Followers of this blog may rightly wonder what happened, after the “Giving African Doctors a Voice” guest blog in May 2016. Millions are bitten by venomous snakes each year, and hundreds of thousands who lack access to good antivenom die or suffer awful injuries. The African Society of Venimology, which consists of doctors and scientists close to the action, put out word that they are facing a serious problem, and that they’re dealing with it whether or not the rest of us get involved. It’s time that I wrote again, to explain how I got drawn into things.

The side conference at the 2016 World Health Assembly, which had been conceived by all concerned as an opportunity to raise awareness of snakebite, was in that sense a success. The story was carried independently by Vice News and by Nature, and about two dozen antivenom manufacturers and researchers around the world posted their distinct points of view on how to address the shortage of antivenom in Africa and beyond. This is clearly an issue whose time has come.

Meanwhile, here in the USA, toxinologists and reptile specialists were facing a related problem, namely that our system for providing antivenom to treat non-native snakebite depends heavily on experimental or “investigational” antivenoms, most of which are available only from zoos, and that our licensed antivenom products are significantly more expensive than elsewhere in the world. Pricing comparisons were made with the Martin Shkreli scandal, and with the rising price of the Epi-Pen. I’ve been caught up in the US side of things because of my organizing role with the Association of Zoos and Aquariums' Antivenom Index, and with a clinical trial of coral snake antivenom, and with some collaborations involving the US FDA.

When calls from the press came into my office last summer, I found myself having to ask, “WHICH antivenom crisis?” to distinguish Africa from the USA. Each time this happened, I felt important very briefly; then I felt very stupid. This was, of course, because good reporters immediately wanted to know how the two issues were connected; and I simply wasn’t enough of an expert on international economics to give them a proper answer.

Well, time passed. And one day I found myself with an international group of people, no one of whom knew the whole answer, either – but among us, maybe we could figure it out. We agreed on some very basic things, particularly related to Africa:

- A lot of people are bitten by snakes, and many of them need antivenom to survive.

- Some manufacturers know how to make good antivenom, at an affordable price per dose if they make a lot of it at one time.

- Many doctors are very good at treating snakebitten patients, if only they have enough of the right antivenom.

- And yet, the world does not have enough treatment for everybody that needs it,most doctors don’t know how to use it, and the per-dose cost to make antivenom in low quantities is high.

It seemed so obvious, from the outside: pharma companies should simply make a whole lot of good antivenom, and doctors should use it. But… that wasn’t happening. Why not?

We talked about how one thing leads to another, in what colleagues have called a vicious circle: a shortage means that there is no antivenom, or that low-quality products prevail. Lack of good medications means that doctors cannot provide good care. Poor care means that patients seek alternatives instead of going to the hospital. A small number of patients at the hospital means the market for antivenom sales is low, which means that quality manufacturers lose interest. And back to the beginning again.

The worst thing about vicious circles is this: if even one part of the system is broken, all the other parts fail. The only way to fix them is to work on everything at once.

- At least one manufacturer needs to make a whole lot of good antivenom.

- Somebody needs to certify that it works and is safe, so fake stuff doesn’t price the good stuff out of the market.

- Somebody needs to buy it and get it into the hospitals.

- More doctors and nurses need to learn how to treat patients properly, and how to obtain the higher quality medicines.

- Everybody with a snakebite needs to go to the hospital for care.

In Mexico, they used to have a problem like Africa’s, but they solved it by attacking every issue simultaneously. Product improvements were put in place simultaneously with government outreach and massive education efforts. Over a decade or two at the end of the last century, Mexico became both a major producer and a major consumer of good antivenom. As a result, mortality from venom injury fell dramatically. Africa now needs to do the same as Mexico once did.

For me, a doctor in the USA, there is one more thing to fix, but it falls outside of the circle because our infrastructure allows for high prices but bars the sale of most world products:

- The USA needs a legal and affordable way to obtain successful world antivenoms, for the rare cases where our citizens are bitten by snakes from other places.

We have some infrastructure issues of our own to confront, to solve this. It’s apparent, however, that the USA must come last in this process. The quality will not go up, nor the shortage end, nor the price come down, simply to satisfy our tiny market. We must depend on places like Africa and Mexico to save us, this time.

Next week, I’ll tell you what the group decided to do.

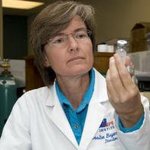

I'm a medical toxinologist, writing to make my field less scary and more understandable to people everywhere.